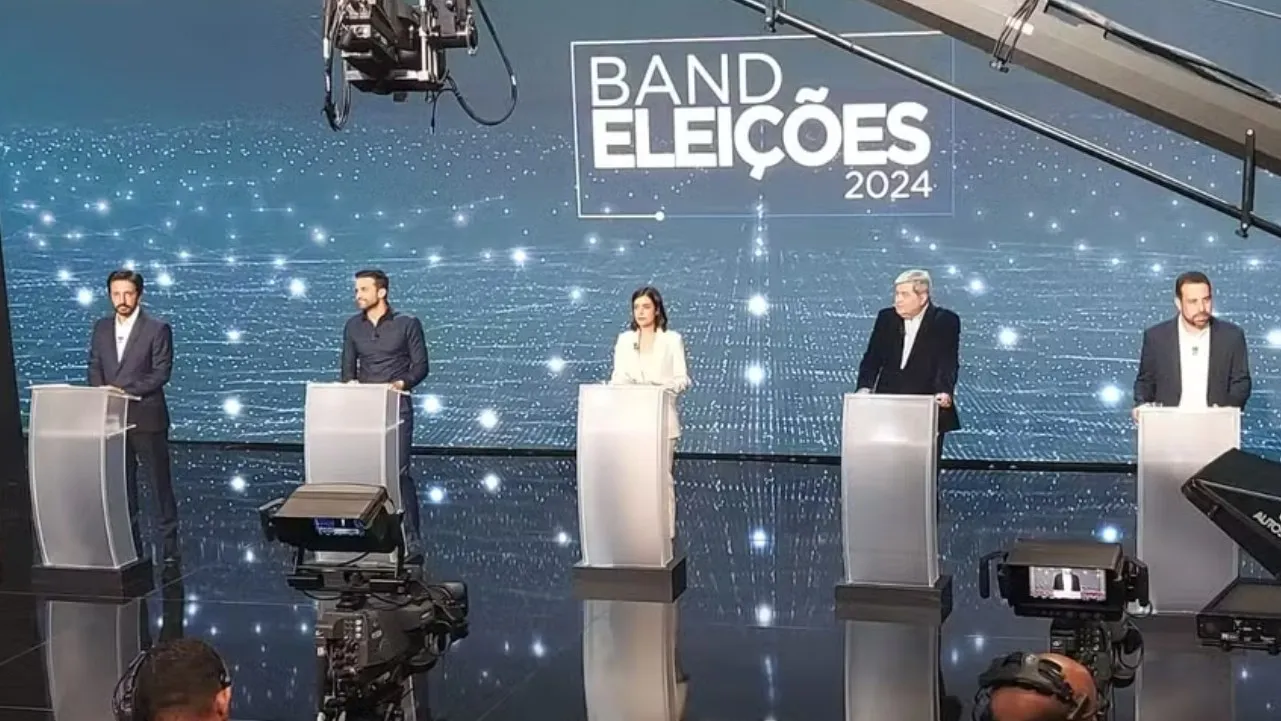

Candidates for Mayor of São Paulo during a recent debate on Band TV network

Every four years, following municipal elections, articles by relatively inexperienced journalists and academics from the Global North surface, often declaring the results a failure for the Brazilian left. Ruling out bad faith, which plays a role in some mainstream papers, this analysis usually stems from a lack of information about Brazil’s complex political landscape. This article, therefore, serves as a primer for Brazil’s upcoming local elections, which will take place in exactly one month from now.

One fact that is commonly overlooked in articles about underwhelming performance in local elections is that even at its peak in 2012, the Workers’ Party (PT) never elected more than 11% of Brazil’s mayors. This might sound odd to those from the US or UK, where only a few parties exist, but Brazil has 29. Furthermore, local politics have traditionally been dominated by elite families tracing their roots to the slave plantation era, wielding sophisticated electoral machines, patronage armies, and dirty tricks that would make Chicago’s notoriously corrupt Mayor Richard J. Daley proud. Often with little ideology beyond a thirst for power, these families habitually switch parties whenever it gives them an advantage. Many mid-sized parties have no vetting process whatsoever, essentially serving as “parties for hire” in the thousands of municipalities across Brazil’s back-country.

Brazil is a vast nation that lacked significant road or rail connections between many states until the 1950s. As a result, some regions had more contact with Portugal than with other parts of Brazil. This isolation led to the rise of hundreds of local and regional political coalitions, often led by powerful families who built long-term alliances through marriages and business deals. A classic example is former President José Sarney, described by a historian I know as “one of those old-fashioned colonels with one son in the Communist Party and another in the Catholic Church.”

Sarney founded PFL (now União Brasil) at the end of the dictatorship but spent much of his career in the Brazilian Democratic Movement Party (MDB). His son Sarney Filho co-founded the Green Party, his daughter Roseana ran for president with PFL, and his allies once controlled the state apparatus of over a dozen parties.

These traditional families sometimes align with the left due to local power struggles or, more rarely, ideological commitment. At the peak of Sarney’s influence, his coalition controlled hundreds of municipal governments in Maranhão, Pará, and Amapá but could never win São Luís’ mayoral office. There, Jackson Lago, great-grandson of a provincial governor from the 1880s, held sway. Lago, a member of the Democratic Workers Party (PDT), was a friend of Fidel Castro and sent his sons to Cuba for medical school. One of his achievements as mayor was building a network of quality public maternity hospitals.

In Pernambuco, the Arraes/Campos family, with roots in 17th Century sugar plantations, wields considerable power. Miguel Arraes, 3-time governor, great-grandfather of current mayor João Campos and grandfather of his 2020 rival Marília Arraes, was a resistance hero during the dictatorship and founded the Brazilian Socialist Party (PSB). Despite his family’s socialist lineage, João Campos had no problem moving right during his Recife mayoral campaign against Marília, then in the PT, red baiting her and her party as godless communists.

Bitter enemies during their electoral face off in 2020, Marília Arraes is now supporting her cousin João Campos for reelection in Recife

This year, 30% of Brazil’s mayors have switched parties since their election—a common trend in local politics as coalitions shift and politicians try to gauge political currents. The biggest beneficiary has been the MDB, which originated as the only opposition party allowed during the 1964-1985 military dictatorship. With 838 mayors and 7,335 city councilors, it remains the largest player in local elections, although it is not very ideologically cohesive, operating more as a patchwork of local power coalitions spanning ideologies from Keynesian centrists to neoliberal opportunists.

In 2012, PT elected its highest number of mayors to date: 624, or 11% of the total. By 2016, following the US-backed coup against Dilma Rousseff and an intense media campaign against the Workers’ Party, its mayoral count dropped 60% to 254. The largest city it kept hold of that year was Rio Branco, capital of Acre, with a population of 400,000 and a GDP of around $1.7 billion USD. The 2020 election results were a mixed blessing; though the number of mayors fell to 182, PT increased its presence in cities over 200,000 by 75%, winning control of four cities with over 400,000 residents and a combined GDP of about $17 billion: Contagem, Juiz de Fora, Mauá, and Diadema. Since Lula took office, 83 mayors have switched to PT, bringing its total to 265 mayors and 2,665 city councilors, making it Brazil’s largest progressive force in mayoral politics.

The second-largest player on the left is the Communist Party of Brazil (PC do B), with 46 mayors and 694 city councilors. Then there’s the Socialism and Liberty Party (PSOL). Over its nearly 20-year existence, PSOL has steadily gained ground in Congress, now having 12 federal deputies, but has struggled to transition from a party of moral critique to one capable of taking power over local governments. Currently, it has 3 mayors and 92 city councilors nationwide but is aiming for a historic win by taking São Paulo’s mayoral seat with Guilherme Boulos.

What to Expect on October 6

The PT, along with its federation partners PC do B and PSB, is expected to make moderate gains. Likely victories include industrial satellite cities in large metropolitan areas—some too new to be dominated by traditional political families—like cities in São Paulo’s ABC region, Contagem in Greater Belo Horizonte, and São Leopoldo in Greater Porto Alegre. PT is also backing strong candidates from other parties in major capital cities like Rio de Janeiro, where incumbent Eduardo Paes (União Brasil) leads with 59%, and Recife, where João Campos (PSB) polls at 74%.

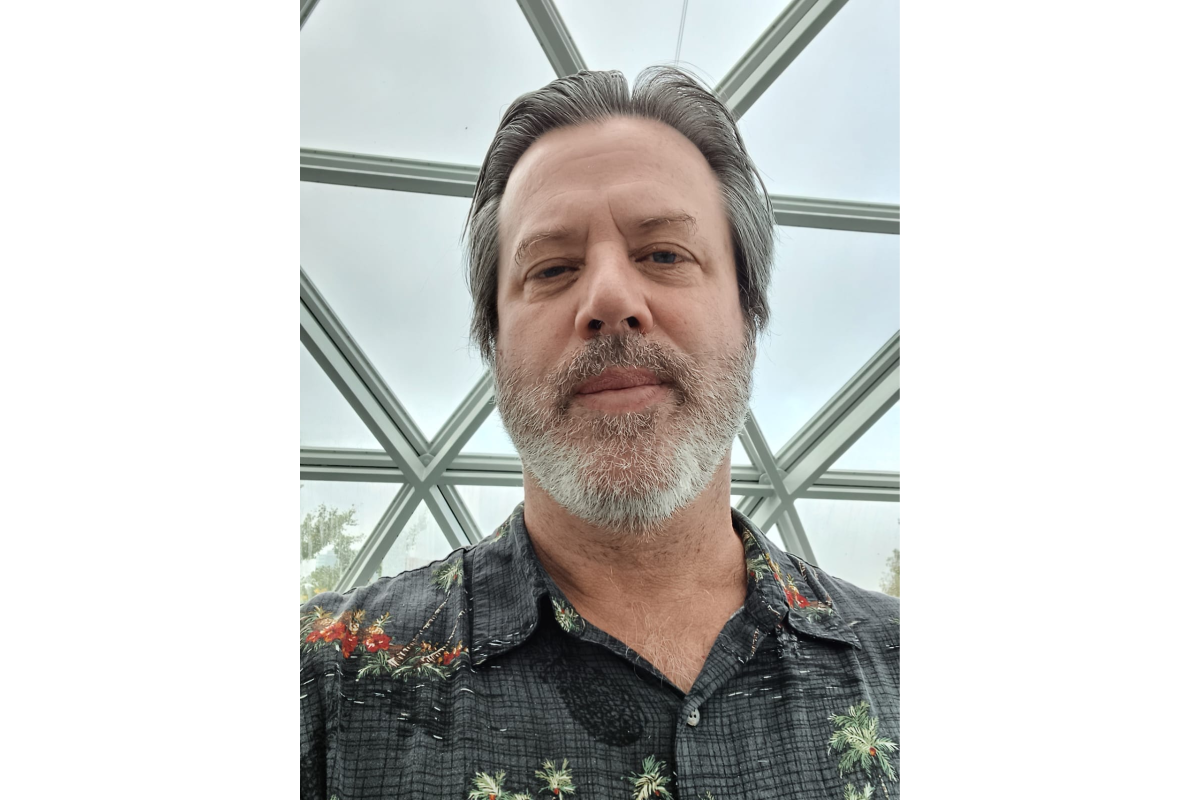

As usual, political chess has created uncomfortable situations where PT is supporting candidates unpopular with its local base, leading to internal grumbling. One such case is Recife. Four years ago, João Campos won on a campaign of negative attacks against PT. This year, due to the national alliance with PSB, PT is supporting him, though he hasn’t included PT on his vice-mayoral ticket, offering only a few cabinet posts. However, Campos’ support for PT’s candidate in neighboring Olinda, Vinícius Castello, almost guarantees a victory there. Castello, young, Black, and from a favela, is a rising star in the Workers’ Party. Another rising star is Dandara Tonantzin, leading the polls in Uberlândia, Minas Gerais’ second-largest city (pop. 760,000). A former teachers’ union leader elected to Congress in 2022, Tonantzin, 30, is Brazil’s only federal deputy who has fulfilled 100% of campaign promises.

Congresswoman Dandara Tonantzin, front-runner in Uberlandia, MG, is one of only 8 women leading in the polls in Brazil’s 50 largest cities.

Porto Alegre is another key race, where Workers’ Party leader Maria do Rosário is polling second and could face incumbent Mayor Sebastião Mello (MDB) in a runoff. Mello has been widely blamed for failing to maintain the city’s flood prevention system, resulting in the worst floods in its history this year. Despite this, he still leads, but debates and the second-round campaign could shift the tide. A victory here would mark a historic return for the left in a city once famous for progressive governance, participatory budgeting, and the World Social Forum.

The Workers’ Party is backing PSOL Congressman Guilherme Boulos for Mayor of São Paulo. In 2020, Boulos reached the second round of the mayoral race, partly thanks to support from multimillionaire businessman Walfrido Warde, a former classmate from USP’s philosophy department. However, after incumbent Bruno Covas, battling terminal cancer, repeatedly labeled him “too radical” in debates, Boulos lost by nearly 20% in the second round.

This year, Boulos has softened his leftist image, inviting several prominent moderates into his campaign team. Running with former Workers’ Party Mayor Marta Suplicy as his vice mayor, he is in a three-way tie for first with two Bolsonaro-backed candidates: incumbent Ricardo Nunes (MDB) and far-right social media influencer Pablo Marçal (PRTB), who was once jailed for fraud. While Boulos is likely to reach the second round, polls show him trailing Nunes by 14% in a potential runoff. If Marçal edges out Nunes to make it into the second round, however, Boulos would have a good chance of winning the election.

Fading Influence

Jair Bolsonaro may still have sway in São Paulo, but his endorsed candidates are struggling in other major cities. In Rio de Janeiro, his pick, Alexandre Ramagem, is polling at 11% against PT-supported incumbent Eduardo Paes’ 59%. In Belo Horizonte, Bolsonaro’s candidate Bruno Engler is third with 13%, while in Recife, Gilson Machado polls at just 9%.

Beyond the big cities, fascinating electoral battles are unfolding in smaller towns across Brazil.

Rural municipalities in Brazil are similar to U.S. counties, often containing multiple towns and covering large areas. In Pesqueira, Pernambuco (population 60,000), the Ororubá Hills are home to the Xukuru indigenous nation, which expanded its reserve from 4,000 to 28,000 hectares after decades of struggle, thanks to the work of Chief Xicão, who was assassinated by ranchers in 1998. Xicão helped unify the Xukuru by reviving religious, linguistic, cultural, and culinary traditions, boosting collective pride. Many who were once hesitant to identify as indigenous now do so openly. Today, 15,000 people live in 26 villages in the hills, and thousands of residents of the town itself also identify as Xukuru.

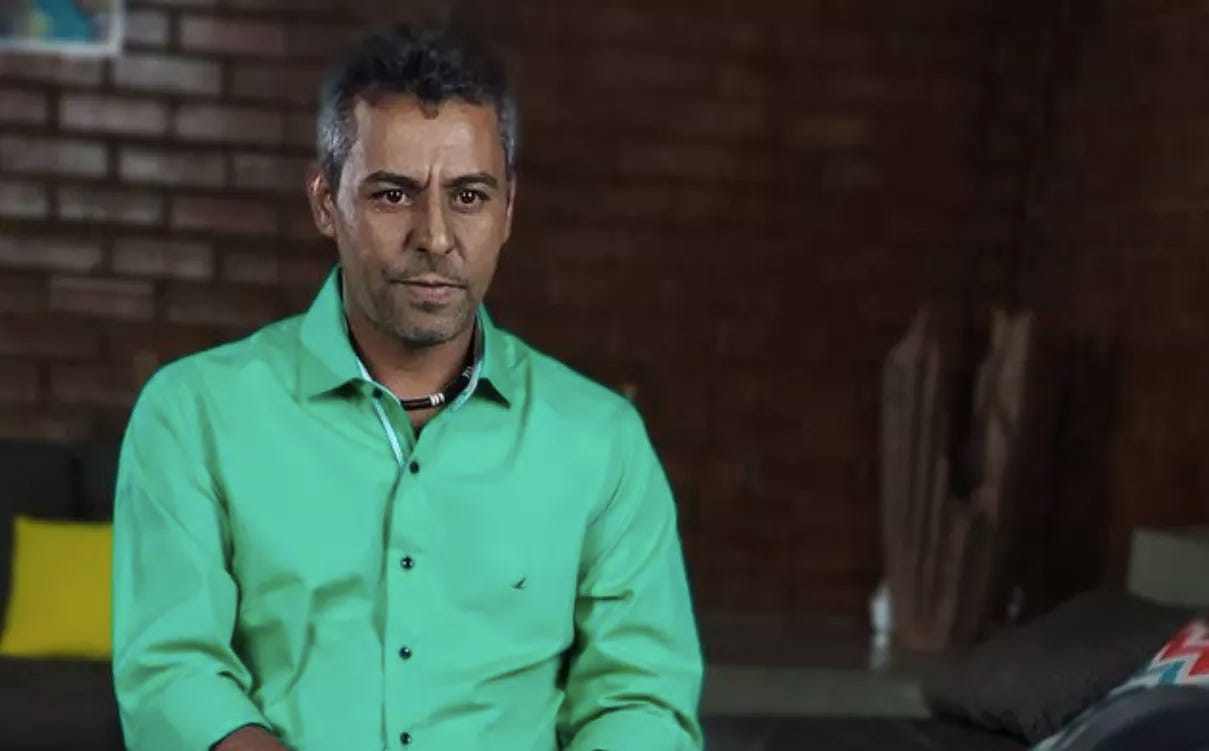

In 2020, Xicão’s son, Chief Marcos Xukuru was elected mayor but was removed months later, accused of inciting violence after his father’s assassination. However, the Xukuru held onto the vice mayor’s office and gained a majority on the city council. After proving his innocence, Chief Marcos was appointed planning commissioner. This year, he is running for mayor again and is the favorite. If he wins, the Xukuru will gain full control of the local government, reversing centuries of oppression by local cattle ranchers.

Chief Marcos Xukuru, currently Pesqueira’s City Planning Commissioner, is running for Mayor this year

With a month to go until Brazil’s elections, the short official campaign season is now underway and Brazil’s strict election laws are now in effect. Although there promises to be a lot more of the same old stories, there are plenty of reasons for people on the left of the political spectrum to feel hopeful. May the best candidates win.

- Article By Brian Mier